It’s no easy task to communicate what the Cunningham sports cars meant to American car enthusiasts in the mid-20th century. America’s postwar autos were worthy enough, but sporting? Not at all. Not since the Auburn Speedsters and Cord 810s of the mid-1930s had American automakers produced cars that appealed to those for whom driving was more than a way of trundling from point A to point B. Thus, in 1951, the 48 states were galvanized by the news that the B. S. Cunningham Company of West Palm Beach, Florida would not only produce a new American sports car, but would also race a team of three cars at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

This was also big news abroad. Briggs Cunningham had made many friends at Le Mans the previous year, when his two Cadillacs had placed 10th and 11th overall, and the announcement he would now build his own cars and race them in the world’s best-known sports-car contest was a sensation of the first magnitude.

The white and blue Cunningham cars would compete officially from 1951 through 1955. They scored 15 race victories, all of them in America, and to qualify to race at Le Mans, Cunningham also produced a handful of road cars that now rank as choice collectors’ items.

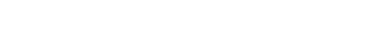

Brake coolant pumps driven off Ferrari engine’s camshafts.

But in one year, 1954, various delays meant that the all-new C6-R would not be ready for the start of the season. Rather than rely on his existing, older machines, Briggs Cunningham decided on a surprising stopgap: a brand-new Ferrari 375 MM.

SO WHO WAS THIS FELLOW CUNNINGHAM? Born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1907 to seriously wealthy parents, Briggs was always a serious car enthusiast. In the early 1930s, he competed in some of the events organized by the Automobile Racing Club of America, and he was fortunate in having the means to pay his own way in racing.

A friend remembered that, “Briggs and I had many discussions about racing together in Europe or importing the European style of road racing to this country in the 1932-33 period.” Also promoting this idea were the Collier brothers, Miles and Sam, both of whom raced in Europe during the 1930s.

In 1951, Cunningham made his first effort at Le Mans with his own car. The Chrysler V8-powered C-2R showed speed but lacked reliability. Two of the three cars retired, while the third finished more than 40 laps behind the winning Jaguar XK-120C.

In parallel with the creation of its C-3 road car, the Florida-based Cunningham outfit designed an all-new racing car for 1952. Designated the C-4R, this was the most durable and successful, and best-known, competition Cunningham. Slimmer by six inches, shorter by 16 inches, and lighter by 990 pounds than the C-2, the C-4R was intended to be faster and better, and in all respects it succeeded.

Returning to Le Mans in ’52, Cunningham entered two C-4Rs and a closed C-4RK. Two cars retired, but the remaining C-4R, co-driven by Briggs himself, finished fourth overall. A C-4R and the C-4RK competed at Le Mans twice more, in 1953 and ’54; they finished seventh and tenth in the first year, then third and fifth in the latter. (Also in 1953, Phil Walters and John Fitch co-drove a C-4R to victory at Sebring, the first-ever race of the newly established World Sports Car Championship.)

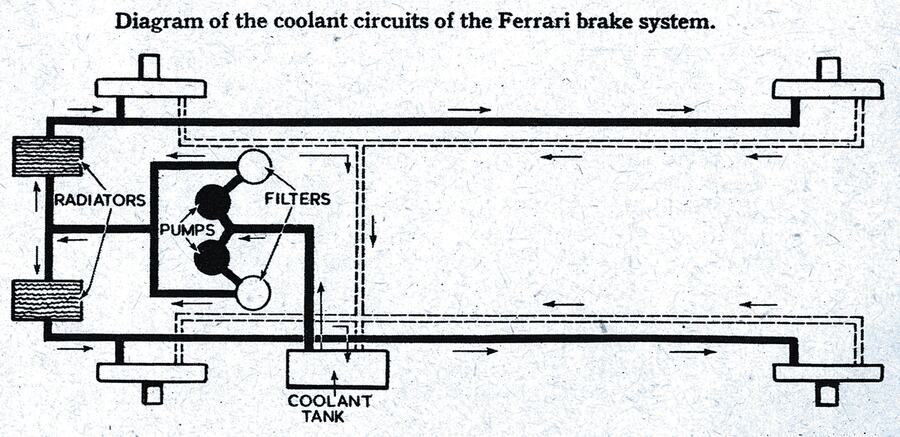

Additional gauges monitored brake-cooling system.

In 1953, in addition to the C-4R, Cunningham fielded the all-new C-5R at Le Mans. The latest machine stayed true to the 310-hp Chrysler V8, and offered huge drum brakes, solid axles front and rear, and sleek bodywork blessed by British designer Reid Railton. While the outlook was promising, the lone C-5R couldn’t defeat the new disc-braked C-Type Jaguars, and eventually finished third overall.

“We could out-speed and out-drive the Jags, but on their brakes alone they easily cruised faster than we could,” explained Walters. “We ran the first two hours at our target speed, which was 104 mph, then raised our sights to catch the Jaguars. We couldn’t do it.”

No all-new Cunninghams were built for Le Mans in 1954. Talks with Mercury Marine’s Carl Kiekhaefer about a new two-stroke inverted V12 engine were under way, so veteran engineer Briggs Weaver designed the new C-6R to receive it. It was decided to use Ferrari’s 4.5-liter V12 as a stopgap, but after realizing the C-6R would not be ready in time, Cunningham simply bought one of the 26 Ferrari 375 MMs that were built in 1953. This car, s/n 0372AM, was an open-top racing spider bodied by Pinin Farina.

Alfred Momo modified Ferrari’s carburetors to prevent fuel starvation during hard cornering.

THE RED FERRARI ARRIVED IN FLORIDA in December 1953, and first competed at Sebring on March 7, 1954. Cunningham’s top driver pairing, Fitch and Walters, had worked their way up to second place when chief mechanic Alfred Momo waved the red car into the pits for a change of spark plugs. The Ferrari returned to the track, but on lap 105 stopped out on the circuit, victim of a suspected broken connecting-rod bearing.

Whatever the problem actually was, Momo and his men were on the case. A week later, the revitalized 375 MM appeared at an SCCA race in Savannah, Georgia, just up the coast from Florida. Bill Spear drove it in a 30-lap race, finishing a very close second to Jim Kimberly in an identical car.

During the subsequent hiatus prior to Le Mans, Cunningham completely transformed his Ferrari. Stripping away Pinin Farina’s efforts, the skilled West Palm Beach crew produced a new, svelte, open racing body, with an almost circular front grille and low-placed headlamps on rounded fenders. Air intakes for the rear brakes sat in subtle screened entries where the rear fenders met the main body. Twin fuel fillers on the rear deck ensured that air went out while gasoline went in. Though specifies are not available, this was certainly a lighter car than the C-4R.

Phil Walters, Briggs Cunningham, John Fitch.

Braking, always a béte noire of the heavy Cunninghams, had always been addressed in different ways. The C-4Rs’ drum brakes featured super-fine lateral finning, and drivers had deceleration gauges on their dashboards so they could control the amount of braking they used. The C-5R featured huge 17-inch drums with centrally balanced shoes, mounted inboard in the air stream.

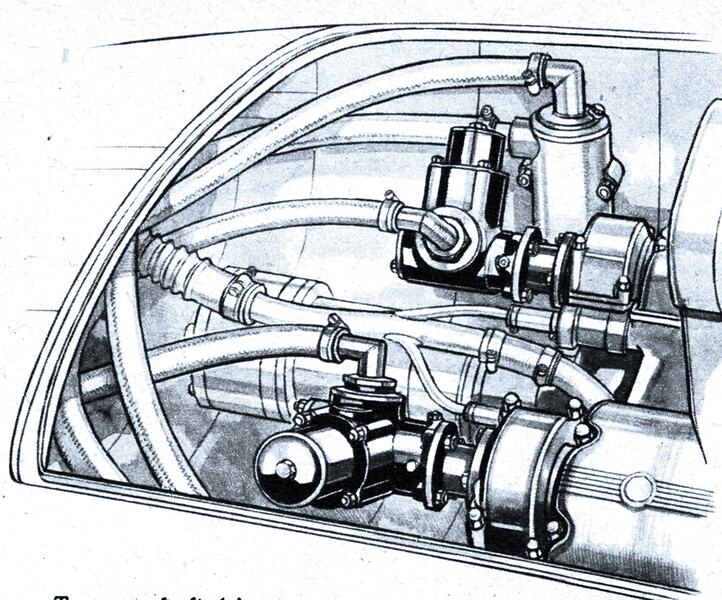

And for the Ferrari, the Cunningham engineers tried something novel: liquid-cooled brakes.

The main man behind this system was Roy Selden Sanford. An engineer who had been filing patents since May 1921, Sanford had come up through Bendix and then Bendix Westinghouse before running his own company Autotyre Co. Inc., in Woodbury, Connecticut, in 1941. On May 3, 1954, he lodged a patent on a new way to reduce brake temperatures. (Four others would share this patent, suggesting it was not a one-man effort.)

Cunningham Ferrari was shipped to and from France on its trailer.

“The conventional drum brake comprises an annular drum of cast iron or steel attached to the vehicle wheel,” wrote Sanford in his patent, “and brake shoes faced with non-metallic friction lining on the axle adapted to engage the metal inner surface of the drum. Because

the lining, often largely composed of asbestos, is a heat insulator, most of the heat developed during braking must be absorbed and dissipated by the metal drum. If the brake is applied with appreciable force for a period of more than a few seconds, the drum heats up and expands, making it necessary—in the case of a hydraulic brake, for example—for the operator to push the brake pedal further down to compensate for this expansion.

“At the same time, the temperature at the engaging surfaces or interface of the drum and lining increases to such an extent that the coefficient of friction of the engaged friction materials falls off rapidly, causing what is commonly known as ‘fade,’ a condition which makes it impossible to stop the vehicle without excessive pedal pressure,” Sanford continued. “In making a single emergency stop from 60 to 70 miles per hour, severe and even dangerous fade is often experienced on many automotive vehicles in use at the present time. This has resulted in a great many serious or fatal accidents. The excessive heat developed under severe braking conditions often raises the temperature of the brake lining above its decomposition temperature, as a result of which rapid disintegration of the lining occurs.

S/n 0372 turned the team’s fastest-ever lap at Le Mans, a 4:26.

“The invention provides a brake mechanism wherein the friction elements which engage during a brake application are a substantially non-metallic brake lining of heat-insulating material on the interior surface of the drum and a friction element or wear surface of copper-based material on the brake shoe,” explained Sanford. “One surface of the friction element closing the brake-shoe cavity engages the lining on the drum. Substantially the entire opposite surface is in direct heat exchange relationship with the circulating cooling liquid in the cavity of the brake shoe.

“The arrangement is such that heat developed at the friction interface is transmitted directly through the friction element to the cooling fluid, so no overheating of the non-metallic lining occurs,” concluded Sanford. “The lining insulates the metal of the drum from the heat developed during a brake application. Consequently, the maximum temperature developed in the metal drum is so low as to eliminate entirely the problem of drum expansion, as well as the problem of drum distortion or checking due to overheating of the drum metal.”

An illustration from Sanford’s patent shows how he ducted coolant through one end of the brake shoe and drained it away at the other. A schematic reveals the way coolant was pumped through filters and then through radiators, delivering glycol-based coolant first to the most-stressed front brakes and then to the rears. Another illustration depicts the pumps driven from the front ends of the drives to the overhead camshafts. Sanford stressed the need for brake shoes fabricated of pure copper that had their “particles fused together to form a solid and continuous mass.”

Ferrari sweeps around outside of Frazer-Nash.

With no small diligence, the system was built and tested for Sanford by Raybestos-Manhattan. It accounted for the peculiar look of the Ferrari’s front end, with two round radiators set into the modest dips between the front fenders and the nose. Gauges that would alert the driver to any major change in the system’s functioning were added to the cockpit.

IN THE RUN-UP TO THE RACE, the Cunningham team enjoyed advance publicity at home when TIME featured Briggs on the cover of its April 26 issue, which chronicled the team’s pursuit of victory at Le Mans.

The article emphasized Cunningham’s ethos of sportsmanship, bolstering the point with quotes from drivers like Stirling Moss, who said Briggs “really built and drove his cars because of his love for the sport…. Briggs is a man I admire very much—a true sportsman.”

Ed Davies races the restored 375 MM with Jim Kimberly’s lucky number 5.

In pre-race practice at Le Mans, the factory Ferraris and Jaguars were fastest, but observers credited a supercharged Aston Martin and the “American Ferrari” with the next-best speeds. This held true in the opening laps of the race, on June 12, with the three works Ferraris seizing the outright lead.

During the race’s fourth hour, the Cunningham-Ferrari, piloted by Fitch and Walters, suddenly went off key. The Momo crew tried all the usual tests, only to find that one of the valvetrain’s rocker arms had broken. With no substitute available, they rejigged the V12 to run on 11 cylinders.

The Ferrari resumed the race in 35th place. Fitch and Walters kept picking off rivals, and had climbed back up to 20th place by 5:00 a.m.—when a grinding noise signaled that a rear-axle bearing had failed. That was the end of their challenge, the Americanized Ferrari ultimately being ranked 27th.

Solace came in the aforementioned third and fifth-place results of the C-4Rs, the team’s best result to date. And while in Europe, Cunningham and his allies paid a visit to Maranello.

“Briggs visited the Ferrari factory with Momo,” wrote Cunningham chronicler Richard Hardman, “where he tackled Enzo personally about the failure of his car at Le Mans. True to form, Ferrari denied any responsibility and stated that his rocker arms do not break. He claimed that the pumps Cunningham had installed to circulate the coolant to the brakes, which were driven off the ends of the camshafts, had been responsible for the failure. To emphasize his lack of sympathy, Enzo accepted the $9.95 for the replacement rocker arm! Briggs left Ferrari in a far from satisfied mood.”

DURING THIS ERA OF U.S. AIR FORCE SUPPORT for motor racing, s/n 0372’s next stop was Lockbourne, Ohio and its airport racetrack in August. Walters finished second behind Jim Kimberly’s similar Ferrari, which would walk away with the SCCA class championship that season. Sanford’s brake-cooling system had been removed, but the distinctive scoops for its radiators remained. Cunningham himself would race the car only once, at Watkins Glen, New York in September, finishing sixth.

After the Glen race, Briggs sold the Ferrari to racer Sherwood Johnston, who had made his bones in the Cunningham equipe. Johnston scored two second places in the 375 MM at Akron, Ohio in October, and enjoyed a similar placing behind the dominant Kimberly car that November in an SCCA National race at March Air Force Base in California, an epic event billed as “East versus West.”

Still driving the Ferrari, Johnston started 1955 with a victory at Eagle Mountain in January, followed by two more wins in races at Fort Pierce in February, and another in May at Cumberland, Ohio. By the end of the year, alternating between the 375 MM and a Jaguar D-Type, he had won the 1955 SCCA National Championship in the C Modified Class.

In mid-1955, with much to do for the Cunningham outfit, Johnston assigned the Ferrari to Dabney Collins, for whom the powerful 375 MM was his first racing car. In five ’55 outings, Collins’ best finish was a fourth at Torrey Pines in California. Colorado enthusiast Temple Buell entered Collins and the unusual Ferrari in a few events in 1956, but thereafter the unique Cunningham-bodied 375 MM left the contemporary racing scene.

“Buell later sold the car to Gary Laughlin of Texas,” wrote Hardman. “From him, the 375 MM went to Bruce Lavachek and Michael Lynch. Michael Sheehan subsequently brokered the sale of the 375 MM to Zambelli, who had the car restored [to its original Pinin Farina configuration] in Italy. The car was advertised for sale in 1994 for $890,000 and was subsequently bought by Ed Davies from Hobe Sound, Florida.”

Since acquiring s/n 0372 in 1994, Davies has both displayed and raced it with robust vigor, including more than a decade of competition in the now defunct Ferrari Maserati Historic Challenge. Though the Ferrari’s unique history is not usually celebrated, it was, and remains, a story well worth telling.