Once I’ve fired the V12, clicked the gear lever into I, and hit the road, it’s like driving into another era. The large wood-rimmed steering wheel, the multitude of instruments and knobs, the smell of old leather—nothing about this 66-year-old Ferrari detracts from the vision of mid-1950s Italy. I drive gently at first, both to get used to this precious, unrestored machine and to let its fluids warm up. Then, on an empty stretch of autostrada, I give the exotic 12-cylinder the spurs and let the speedometer run until it ticks the 200-kph mark.

Ferrari began seriously mass-producing cars intended for road use in those same 1950s. The company had already built coupes and GTs in small numbers, but these were still heavily competition-oriented. The turnaround came at the 1956 Geneva Motor Show, where Ferrari showed the 250 GT: a prototype for a refined 12-cylinder coupe made for grand rides, a Gran Turismo in ultimate form.

Pinin Farina would make the bodies for these GTs in a new, large workshop in Grugliasco, west of Turin. At least that was the plan, but construction delays and commitments to Fiat, Alfa Romeo, and Lancia meant the coachbuilder could only fulfil its contract with Ferrari by outsourcing the job to Carrozzeria Boano in Turin.

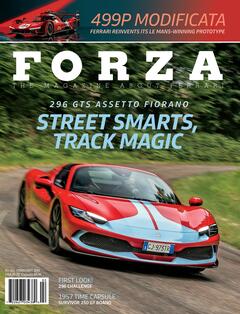

The 250 GTs made there by Felice Mario Boano had a different style from Pinin Farina’s. They were recognizable by their more slender stature, unbroken straight waistline, and lower roof, which made them look a lot sportier. The Ferrari starring in these pages is one of them.

The 250 GT production process underwent another change when Boano started a new career at Fiat, where he would shape its new styling center. He sold his company to Ezio Ellena and his son-in-law Luciano Pollo, who renamed the company Carrozzeria Ellena and continued to build Ferraris. However, Ellena gave its 250 GTs a higher roof and abandoned the three-quarter windows in the doors.

Carrozzeria Boano bodied a total of 68 Ferrari 250 GTs, 14 of which had all-aluminum skin. Ellena completed another 50 of them, but you won’t find the names Boano or Ellena on their respective 250 GTs, as both houses had done their fine work as subcontractors. And when Pinin Farina was finally ready to take over production, in 1958, it did so with a considerably different, and much less beautiful, design.

OUR FEATURED 250 GT BOANO (s/n 0645GT) resides in the collection of a Dutch enthusiast, who purchased it via broker Simon Kidston. This Ferrari is unique, not only because it is unrestored but also because it is probably the only one that was used for rallying. Several wealthy owners did compete with their Boanos in period, but those Ferraris appeared in the Mille Miglia, the Tour de France, and various other races, up to and including Bahamas Speed Week.

According to Kidston’s dossier, s/n 0645’s history was researched by marque experts Marcel Massini and Marc Rabineau. There’s far too much detail to go into, but, after being completed in April 1957, the Ferrari became the official property of Frenchman Maurice Parucci, CEO of Générale Immobilière de la Côte d’Azur, in early 1958. The car was already registered in Monaco by then, with registration number 3258 (as seen in period photographs).

The Ferrari was originally painted Marrone, a chestnut brown, but was soon changed to its current color, Verde Riviera, probably at the request of buyer Parucci. Upon delivery, the Ferrari was already fitted with some sporting extras, including an aluminum hood and trunk lid, powerful Marchal 660/760 foglights in the grille, and Pilote X Racing tires by Michelin.

Parucci’s acquisition involved Lucien Jean Bonnet, director of Garage Méditerranée in Nice, which specialized in sports cars. Both Bonnet and Parucci were keen motorsport enthusiasts, and had independently driven the Mille Miglia several times: Parucci in Panhards (he was co-founder of the Panhard Racing Team) and Bonnet in Renault 4CVs and also a Panhard. Bonnet also regularly competed in local hillclimbs.

Together, Bonnet and Parucci began enjoying the new Ferrari—in perhaps a surprising way, as instead of track racing they went for rallies. According to Massini, the pair immediately entered the Boano in the Rallye de Monte Carlo in January 1958. It was an historic moment, the debut of the Cavallino Rampante in the famous rally.

The number of participants that year was particularly large, but the snowfall was so exceptionally heavy that 243 cars dropped out before the finish of the first stage, either due to accidents or simply not achieving the required times. Bonnet and Parucci, with start number 330, also gave up, presumably because they found the rally too intense for their brand-new Ferrari. Out of more than 300 starters, only 59 eventually completed the rally (which was won by Frenchmen Feret Jacques and Monraisse Guy in a Renault Dauphine).

In early March, Bonnet and Parucci fared considerably better in the 500-kilometer Rally Marseille-Provence, also known as Rallye Pétrole-Provence. In better weather, they were able to take advantage of the Ferrari’s power on the Miramas circuit and at Mont Ventoux, and finished first in their class.

In April, the duo drove the 435-mile Rallye de la Lavande, from Carpentras to Cagnes-sur-Mer, criss-crossing Provence. The Boano, with start number 234, must have been in its element there too, but its final result is unfortunately unknown.

In July, Bonnet and Parucci teammed up for the Criterium Internationale de la Montagne, also known as the Coupes des Alpes. Without doubt one of the toughest rallies on the calendar, it featured many mountain passes, including the infamous Col d’Izoard, the Galibier, and the Stelvio.

A Shell film of the ’58 Coupe des Alpes can be found on YouTube. The hairs on my neck sometimes stood on end as I watched how hard the cars were pushed over the narrow, unpaved passes, often losing fenders or even doors along the way. You’ll spot the Boano passing by at 4:42, 7:10, and 7:18 on the timeline, but it then disappears. Once again, Bonnet and Parucci gave up, possibly due to problems with the brakes during the descents or perhaps because they simply found the event too tough. After all, 30 of the 55 participants did not make it to the finish.

Although Bonnet and Parucci entered the Ferrari in September’s Tour de France Automobile, they did not appear at the start. It was the end of s/n 0645’s competition career, and in late ’58 Parucci concluded his own involvement in motorsport, devoting his full attention to his business.

Bonnet reportedly still used the Ferrari for some time, although not competitively. He instead turned to monopostos and even tried his hand in Formula 1. Driving a Cooper T45 he entered the ’59 Monaco Grand Prix, but failed to qualify for the race itself. He debuted in Formula Junior in 1961, and in ’62 raced in the Campionato Italiano Formula Junior. But his career came to an abrupt end on August 19th that year, during a preliminary race of the Gran Premio Mediterraneo Formula 1 in Sicily. When Bonnet swerved to avoid an errant wheel on the track, his Lotus 22 Ford flipped and he was thrown out and killed, at age 39.

By this time, the Boano was owned by one Guy Gravier, in Nice, who kept the car in his collection until April 1986. Gravier did not use it much, beyond perhaps some outings along the French coast; his only known substantial drive of the green 250 GT was a visit to Modena and Maranello, in September 1983, for the International Ferrari Days.

Three years later, Gravier sold the Boano to classic car dealer Massimo Colombo. Since then, s/n 0645 has passed through several hands, including those of collector Massimo Sordi. The Ferrari was hardly used during that period, and in 2015 still had fewer than 62,000 kilometers on the odometer—meaning it had only been driven 5,000 kilometers (just over 3,100 miles) in the previous 34 years, or less than 150 kilometers (93 miles) per annum. Eventually, the Boano ended up with its current Dutch owner via Kidston, who gave me the opportunity to add some kilometers of my own.

THIS FERRARI IS A TIME TRAVELER in every way. It looks excellent, with only barely noticeable scratches and dents found here and there. I can see its age mostly in the interior, on the door panels and floor mats. Next to the accelerator pedal, the carpet covering the transmission tunnel is completely worn through, revealing bare metal.

A few decades ago, it would have been entirely appropriate to renew the fabric, the door panels, and the battered leather, all part of being a good caretaker of a precious thoroughbred. Today, however, few owners would dare even consider that, let alone a restoration. Presented with a Ferrari that has travelled through time, from the late 1950s to the present, bearing only traces of what it was made for, you don’t bring it back to as-new condition! Instead, you continue its unique history by cherishing it—and driving it. Once I made this mental leap, it suddenly felt a lot easier to embark on a hefty drive.

First, it’s time to walk around this Ferrari Classiche-certified, matching-numbers Boano, where even the glass is original; the 1955 “Securit” etched into the windshield is still easy to read. Under the hood lives the famous Colombo V12, with its own ignition for each cylinder bank and adorned with three double Weber carburetors, size 36. Louvers in the inner fenders help hot air escape from the engine compartment. The Ferrari of course rolls on Borrani’s wire wheels, shod with Michelin’s Cup tires of the era: Pilote X Racing, size 600 × 16, the same type it was delivered with.

Climbing inside, I drop onto a comfortable, fairly soft-sprung seat, which offers little lateral support. That’s no bother, however, as I’m close to the door and there’s plenty of room to brace myself in place with my legs. The roof is low—I’m 6-foot-1 and the headliner brushes my hair—as are the windows, but there’s plenty of side visibility, plus one exterior mirror on the left. The interior mirror is minuscule and quite weathered, and is accompanied by two dark green Perspex sun visors.

The dashboard wears the same paint as the exterior sheet metal. A whole row of instruments (all but the clock from Veglia) is embedded in the dash, with starring roles for the speedometer and tachometer. The latter features a stripe of red at 7,000 rpm while the former reaches 300 kph (186 mph), quite ambitious for the period. According to the factory, the Boano’s actual top speed was around 137 mph, and it sprinted from 0 to 62 mph in roughly eight seconds.

The large Nardi steering wheel sits quite close, forcing me to keep my arms “dog-eared.” This turns out not to be all that awkward, as it gives me more leverage over the unassisted steering. There’s a heater dangling under the center of the dash, but since it’s a warm day I instead roll down the window, a feat which requires rotating the crank a full 8.5 times. The underside of the dash also abounds with rocker and rotary switches, virtually none of which are labeled. The lights and turn signals are easy to find, however, and that’s enough for the moment.

The 12-cylinder fires up immediately. After being encouraged by a few prods of the throttle, it switches to a calm idle. Ferrari’s familiar open shift gate is nowhere to be seen, and shifting the fully synchronized gearbox requires some attention, as its pattern is reversed from the norm: I and II are on the right and III and IV on the left. Spring tension ensures that the lever is automatically pulled to the position between III and IV when I want to shift up, and the strokes I have to make with the lever are small and tight, making shifting a pleasure.

The 3-liter engine sounds nice, warm, and melodious, with only a moderate amount of aggression in it, just as it should in a Gran Turismo. The V12 is smooth and takes throttle just fine, even at low revs. When I accelerate briskly above 3,000 rpm, it lets me hear that it has the heart of a thoroughbred sports car and is happy to cover as many meters of autostrada as quickly as I’d like.

At 100 kph in fourth gear, the rev counter reads 3,000. It’s certainly not whisper-quiet inside the Boano, but there is a pleasant calmness. This is a car in which I envision myself travelling long distances. At 6,000 rpm, the speedometer would indicate 200 kph—and since there are still 1,000 revs to go, Ferrari’s claimed top speed seems very plausible.

Disc brakes were already around when Mario Boano made the bodywork for this 250 GT. Jaguar raced with them as early as 1953, while Citroen supplied them as standard on the DS 19 back in ’55. Ferrari arrived more than fashionably late to this particular party, however, so the Boano features drums all around—albeit very large ones, which fill the Borranis superbly. The pedal has a slightly longer free stroke than expected, so I have to brake a fraction earlier than I’m used to. I also have to push firmly, but am then rewarded with fine deceleration, good enough to drive the Ferrari at speed with confidence.

The steering feels pretty dead, as is the case with many cars of the era. Some feeling creeps in when I turn the steering wheel away from center, but I can more easily see from the nose’s direction that something is happening underneath rather than feeling it.

This changes once I’ve built up enough confidence in the Boano to drive it with bravado. As soon as I dive into corners at such speed that the body tilts, more weight is put on the outer wheels, the tall sidewalls of the Michelins flex slightly, and the Ferrari starts talking to me. And this, I realize, is how Bonnet and Parucci drove it, when they stormed up Mont Ventoux with a gloriously roaring V12 during the ’58 Rallye de la Lavande.

Unrestored, with an exceptional patina and astonishingly low mileage, s/n 0645 nonetheless deserves to be driven—more miles will only add to the Ferrari’s appeal, as well as its owner’s enjoyment. Besides, there is still some unfinished business in its history, namely the ’58 Tour de France for which the Boano was registered but never started. Today, that rally is still being held, under the name Tour Auto, across France, with tests on racetracks, hillclimbs, and perhaps a run up Mont Ventoux. The 2024 edition is coming up next April, and I’ll happily volunteer my services as a co-pilot if needed.